The Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA), 42 U.S.C. §300f et seq. or Pub. L. 93-523, was signed into law by President Gerald Ford on 16 December 1974 which makes today SDWA’s birthday! While President Ford is better known for pardoning President Richard Nixon, signing SWDA is probably his most consequential action currently. I’ve previously written on the SDWA regulatory process and one of its amendments, the America’s Water Infrastructure Act of 2018, was the first post on this blog. In broad brushes, I intend to briefly cover pre-SDWA, as well as the build-up, an overview, brief history, and impact of SDWA. As with everything I write here, I am acting in my own personal capacity not representing my employer.

Pre-SDWA

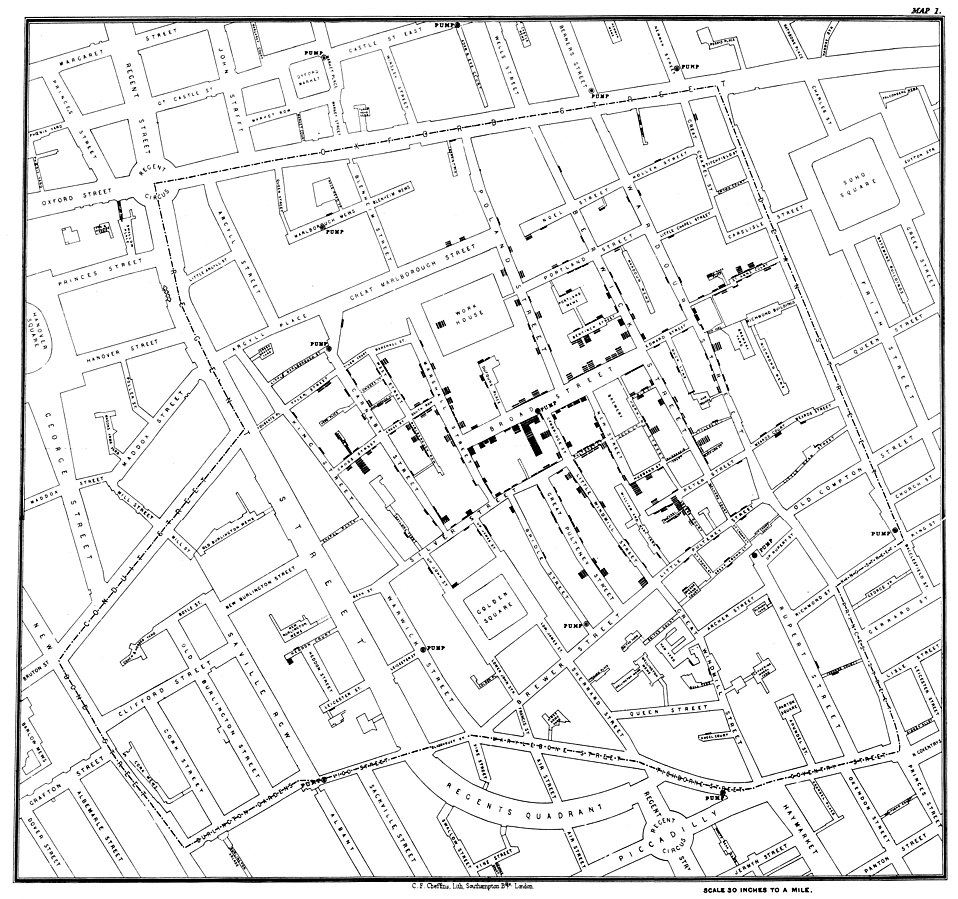

As I’ve written about before, drinking water was famously acknowledged as disease vector by John Snow and the Broad Street Pump.

The SDWA was the first comprehensive regulatory framework for drinking water in the United States. Prior to SDWA, federal regulation of drinking water began in 1914 when the US Public Health Service regulated interstate water carriers such as ships or railroads. These standards were expanded in 1925, 1946, and 1962. The ’62 standards covering 28 substances, were the most comprehensive pre-SDWA federal drinking water standards and all 50 states had adopted them with varying modifications.

SDWA Build-up

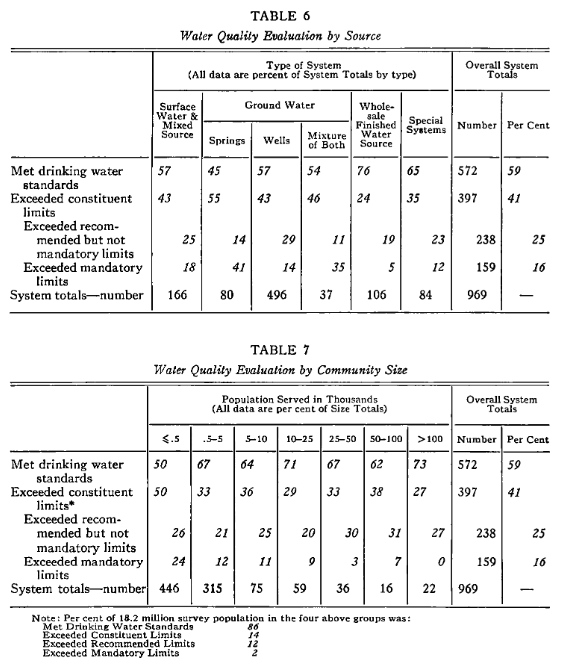

The ’62 standards did not include many industrial or agricultural chemicals which found their way into drinking water supplies at the time. Concerns around this led to the federal government commissioning water system surveys, a famous one in 1969 (published by none other than AWWA!), showed that only ≈60% of surveyed water systems met the ’62 USPHS standards. Over half of the systems surveyed had major deficiencies involving disinfection, clarification, or pressure. A Region VI study found 36 chemicals in treated drinking water sourced from the Mississippi River in Louisiana. This increasing awareness lead to a constellation of laws which work in concert with SDWA such as the Clean Water Act, CERCLA, RCRA, and many others.

SDWA Overview

SDWA aims to protect public water supplies, it does not apply to private wells which serve about 13 million people in the US. Under SDWA, a public water supply/system does not refer to who owns it but rather if the system meets certain characteristics such as having more than 15 service connections or serving greater than 25 people so, by SDWA, a public water system can be privately owned. SDWA divides public water systems into categories based on characteristics such as where they serve customers and how often they serve the same people; systems with different characteristics have different rules. The original 1974 SDWA was heavily predicated on the ’62 USPHS standards with added requirements for monitoring, analytical standards, reporting results, record keeping, notification for failing to meet standards, and adding standards.

SDWA has a few seemingly counterintuitive features. Chief among them for the public is the concept of primacy. While SDWA is a federal standard and federal regulators determine the levels of contaminants allowed in drinking water, enforcement authority is delegated to more local bodies that meet specific criteria. Every state except of Wyoming, the inhabited territories, the District of Columbia, and the Navajo Nation all have primacy, or enforcement authority for drinking water.

SDWA History

While there have been several amendments to SDWA, the main amendments occurred in 1986, and 1996. After SDWA’s passage, Congress became frustrated by the slow regulatory pace at the EPA. The 1986 Amendments required EPA to set standards for 83 contaminants and make determinations to regulate an additional 25 contaminants every three years as well as to specify the best available treatment technology for removing each regulated contaminant from drinking water among other provisions. EPA categorically missed statutorily imposed deadlines and there were questions about enforcement efficacy. In the words of EPA’s 1996 water head (known as the Assistant Administrator for the Office of Water), Robert Perciasepe, in testimony to Congress on 31 January said the ’86 amendments created a “regulatory treadmill [which] dilutes limited resources on lower priority contaminants and as a consequence may hinder more rapid progress on high-priority contaminants.” Increased public scrutiny brought about major changes to SDWA in 1996. These amendments focused regulation on through risk-based standard setting, increased funding, created “right-to-know” provisions, and strengthen enforcement authorities among other provisions.

SDWA’s Impact / Conclusions

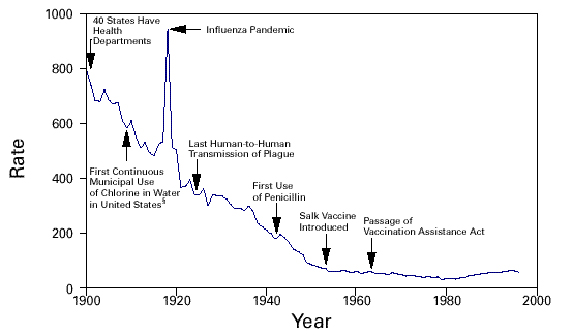

As of third quarter 2024, federal drinking water regulations apply to approximately 143,539 privately and publicly owned water systems and cover ≈87% of the US population. The US is a far cry from circa 40% of surveyed water systems failing basic standards. SDWA has achieved better drinking water quality across the United States. Water-related gastrointestinal disease outbreaks have reduced considerably with SDWA while surveillance and detection have improved. SDWA has been successful in reducing risks and improving public health through dedicated water professionals at the utility, primacy agency, and federal levels. I am proud to play a role in that joint enterprise.