Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a ubiquitous emerging public health threat. PFAS terminology can be extremely confusing because it looks like an alphabet soup of similar acronyms. This article is the second of two on PFAS terminology. The first intended to provide an overview of PFAS structure (including what counts as PFAS), this one intends to help demystify PFAS terminology and nomenclature. These are part of a broader series on PFAS including their serendipitous discovery.

Introduction

PFAS are a large chemical class generally produced in industrial processes which do not produce pure substances; often impurities are introduced to the end product. An isomer is a compound with the same chemical composition as another compound but a different chemical structure. In the PFAS world the terms “branched” and “linear” refer to differing isomers. As a short hand, people often mean all isomers of a particular compound when they name it. PFAS can also be cyclic in which case the linear/branched nomenclature breaks down.

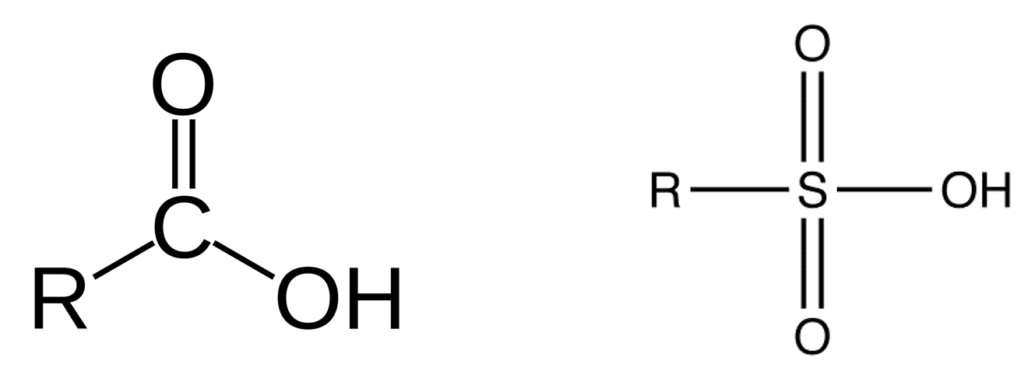

Linear and branched non-polymeric PFAS are typically composed of two parts: a hydrophobic as well as lipophobic fluorinated carbon backbone and a typically polar hydrophilic functional group. The suffix philic means an affinity for and phobic means fear or aversion, the prefix hydro means water and lipo is for lipid or fat.

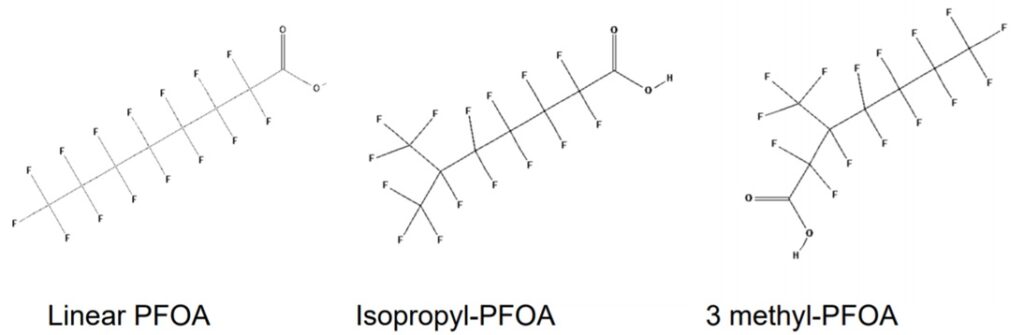

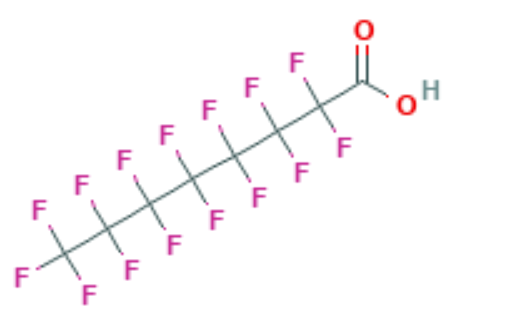

Structural analogues are compounds similar to other compounds but differing in one aspect. Structural analogues are also known as congeners. An example could be homologues. PFAS with the same functional groups differing in the number of carbons and fluorine atoms in the backbone are known as homologue series. For example, perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids with 4 fully saturated carbons in the backbone to 12 fully saturated carbons in the backbone would form a homologue series. A homologue group includes all linear and branched carboxylic acids with the same number of carbons in the backbone. For example, the C8 carboxylic homologue group includes linear perfluoroalkyloctanoic acid (PFOA), isopropyl-PFOA, and 3-methyl-PFOA; there are 89 total theoretically possible C8 carboxylic homologue congeners although in addition to the linear form. The picture below shows some C8 carboxylic homologue congeners, while technically separate compounds for ease they are often referred to as a singular entity.

Naming Systems

There are 5 main systematic methods currently in use to name fluorinated compounds: the International Union for Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) nomenclature, the perfluoro nomenclature, code numbers, Chemical Abstract Service (CAS) nomenclature, and F-nomenclature systems. Due to strong similarities, fluorinated organic compounds tend to follow hydrocarbon naming conventions.

Basic Conventions

Many PFAS are acids and may exist as a protonated or anionic form as well as a mixture of both depending on the pH. The pKa values tend to be quite small and scientists generally refer to PFAS with acid functionalities as “acids” rather than carboxylates, sulfonates, or the correct terms even though the dissociated forms may be the only relevant forms. Scientists refer to both the protonated and ionized forms by the same acronyms. Most perfluorinated acids are environmentally anions. Some labs report results in the acidic form, some report anions, and some a mixture. Many times, perfluorinated carboxylic acids are reported as acids (for example perfluorooctanoic acid instead of perfluorooctanoate) and perfluoroalkyl sulfonic acids as anions (for example perfluorooctane sulfonate instead of perfluorooctane sulfonic acid). This has caused confusion. The labs are really measuring the concentration of perfluorinated acid anions present; when the lab reports an acid the lab adjusts for the cation. Most sulfonate standards are prepared from salts and the mass adjusted which is why they are often reported that way. This is especially true for PFHxS, PFOS, ADONA, 9Cl-PF3ONS and 11Cl-PF3OUdS. Section 7.2.3 of EPA Method 537.1 details how to convert to adjust for this.

IUPAC Nomenclature

IUPAC Nomenclature systematically establishes unambiguous, unique, uniform, and consistent compound names based on their chemical structure. IUPAC Nomenclature can be used for all organic compounds and is not specific to PFAS. IUPAC Nomenclature is quite literally a book containing many precedents and steps however, the general simplified steps for IUPAC Nomenclature are:

- Identify the longest carbon chain. The longest carbon chain is also known as the “parent chain.”

- Identify any groups off the parent chain.

- Number the carbons in the parent chain so that the groups off the parent chain have the lowest number.

- Number and name the groups just counted.

- Put all the name components together in alphabetical order; prefixes such as di- are not used for alphabetical order.

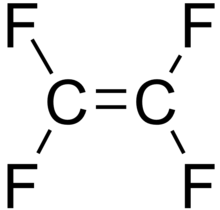

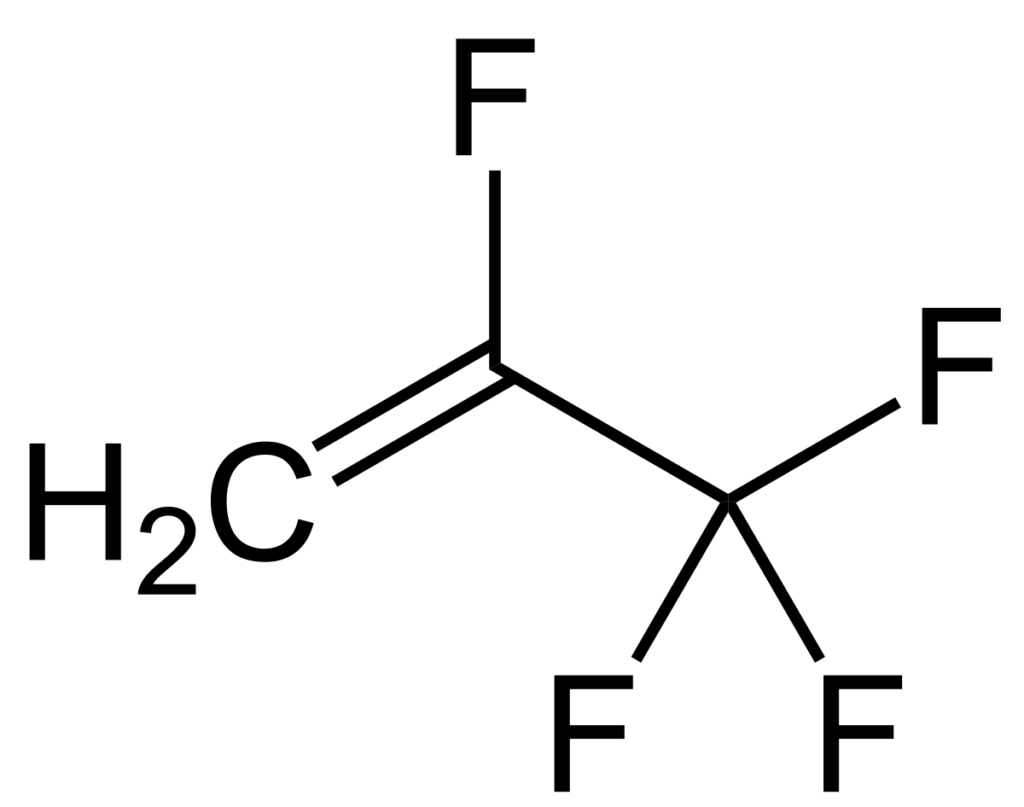

For example, C2F4 is tetrafluoroethene, shown below, is the simplest perfluorinated alkene (fully saturated carbon backbone with no functional groups).

Perfluoro Nomenclature

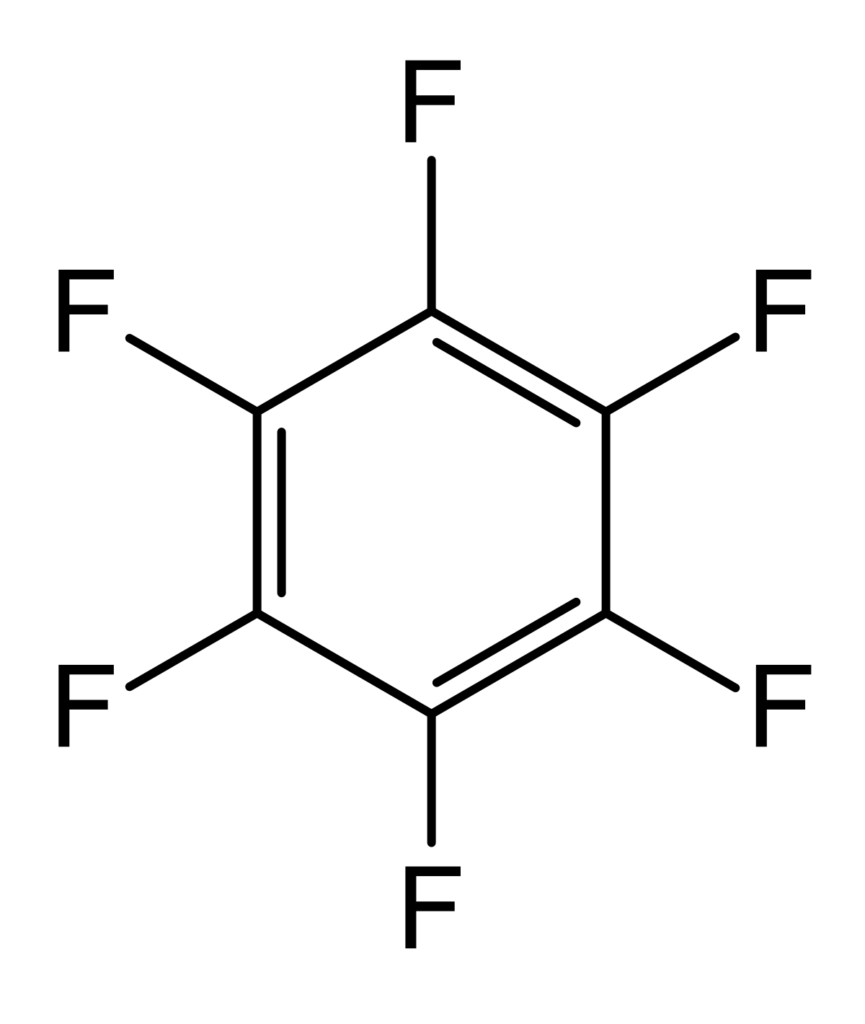

Perfluoro Nomenclature only applied to perfluoroalkyl substances. It is commonly used to quickly identify fully fluorine saturated carbon compounds. For shorter substances using IUPAC naming conventions is still easy and understandable. Most chemists would immediately understand that hexafluorobenzene (C6F6 – shown below) has a cyclic fully saturated carbon backbone. However, for longer compounds such as pentadecafluorooctanoic acid it is difficult to readily tell which is the motivation for Perfluoro Nomenclature. The proper IUPAC name for that compound is actually: 2,2,3,3,4,4,5,5,6,6,7,7,8,8,8-pentadecafluorooctanoic acid which is fairly cumbersome to use further motivating Perfluoro Nomenclature. The pentadecafluoro refers to the 15 fluorine atoms, octanoic acid refers to a carboxylic acid functional group that is off the 8th carbon in a chain. This compound is pictured under hexafluorobenzene.

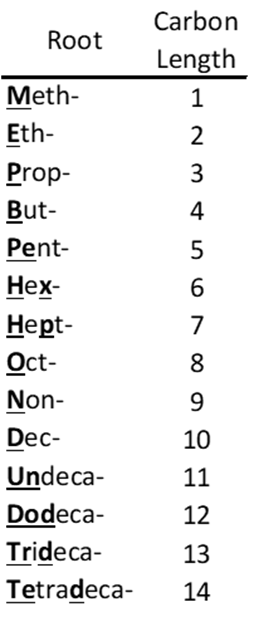

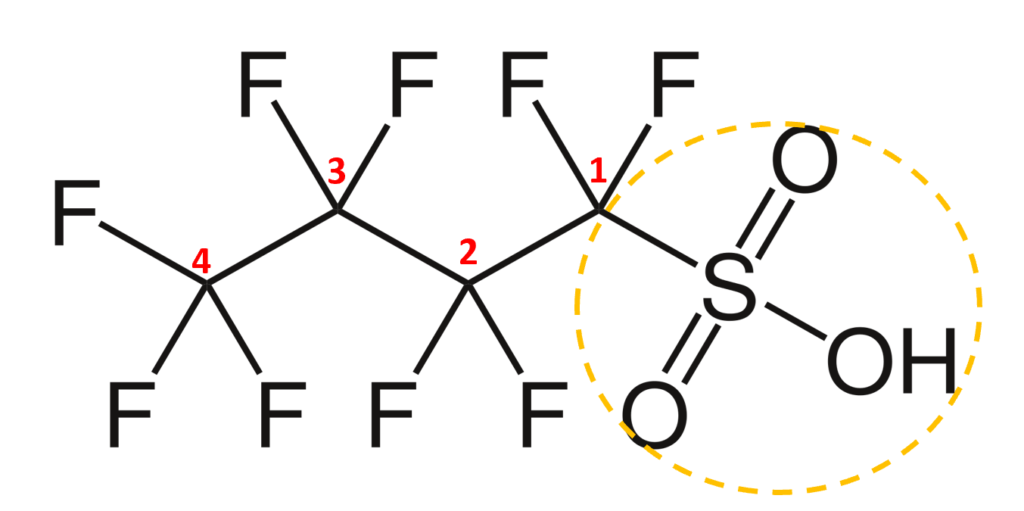

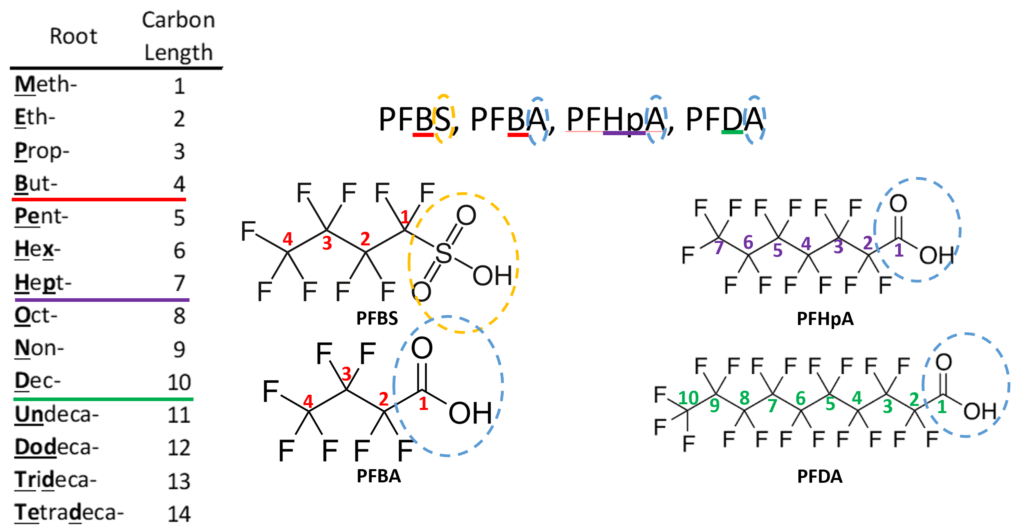

Perfluoro Nomenclature uses the prefix perfluoro along with standard hydrocarbon nomenclature. This simplified naming system has been in place since the 1950s and is the most common naming system among practitioners. The acronyms developed from this system follow a simple pattern; they all start with the prefix PF for perfluoro then have a root based on the carbon backbone, and a suffix denoting the functional group. The table below gives the roots for C1-C14 and the two most common functional group abbreviations are A for carboxylic acids as well as S for sulfonic acids.

The acronym itself provides a well-defined structure for the PFAS compound. For instance perfluorobutanesulfonic acid or PFBS is shown below. The front letters PF stand for per-fluoroalkyl, the B stands for but-, -ane shows there are only single bonds in the carbon backbone which is implied, and the S is for sulfonic acid. PFBA, PFHpA, and PFDA are also shown.

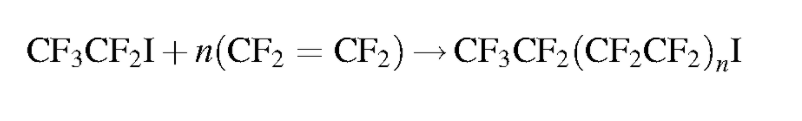

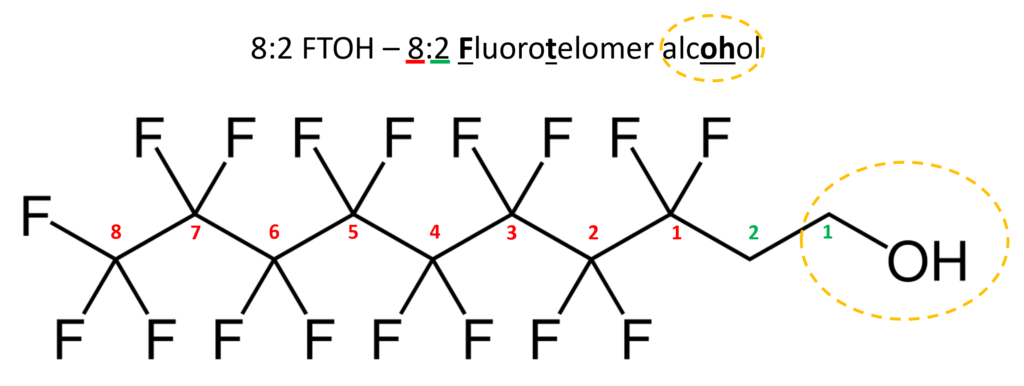

Should it be necessary to refer to a specific salt for a perfluorinated compound it is customary to write the salt’s common abbreviation in front of the standard perfluorinated abbreviation then drop the acid from the name. For instance, the ammonium salt of PFOA, ammonium perfluorooctanoate, is often abbreviated APFO. While not strictly included in the perfluorinated system, some polyfluoroalkyl compounds can degrade into perfluorinated compounds. A polyfluoroalkyl compound is one where the carbon backbone is not fully fluorinated. An important subset of polyfluoroalkyl substances are fluorotelomers. Fluorotelomers are substances made from the most common industrial process for perfluorinated compounds, telomerization. In telomerization a transfer agent, known as a telogen, reacts with a polymerizable taxogen (monomer) to produce a telomer. Generally in commercial production, perfluoroethyl (pentafluoroethyl) iodide as a telogen reacts with tetrafluoroethylene oligomers as taxogens, most commonly tetrafluoroethylene, to produce telomer perfluoroalkyl iodide polymers. The perfluoroalkyl iodide polymers are then converted into other substances.

Similar to perfluorinated acids, fluorotelomer substances are typically named for their functional group. Fluorotelomers often are abbreviated FT followed by their functional group. There are often numbers preceding the abbreviation such as 8:2. The first number represents the total perfluorinated carbon atoms and the second number the unsaturated carbons atoms.

Code numbers

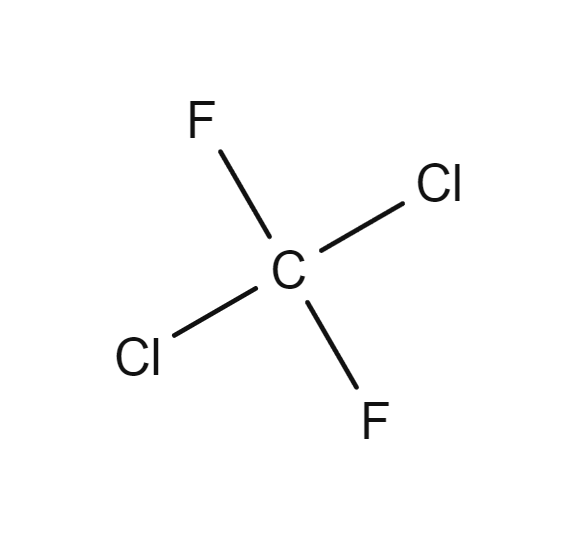

Systematic names are fantastic in precision but can be difficult to use. Unless you work with compounds frequently, memorizing the prefix structures and extra rules, which were glossed over in this article can represent an annoying time commitment. Additionally, it can be error prone especially to infrequent or new users. Industrial PFAS manufacturers such as ICI Fluoropolymers, ISC, DuPont, and 3M developed inhouse shorthands for PFAS. As the inhouse systems were not meant for the general public this initially caused confusion. In Organofluorine Chemistry dichlorodifluoromethane (CF2Cl2) is used as an example to illustrate this. Dichlorodifluoromethane was known as Freon-12 by DuPont, Arcton-6 by ICI, and Isceon-122 by ISC. By 1957 a standardized code number system based on DuPont’s system was adopted and formalized as The American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) Standard 34 which was last updated in 2019. DuPont’s system was first developed by Albert Henne, Thomas Midgley, and Robert McNary in 1929.

Dichlorodifluoromethane (CF2Cl2), better known as Freon-12, was formerly a popular chlorofluorocarbon halomethane refrigerant now banned under the Montreal Protocol. It is now only allowed as a fire suppressant in submarines and aircraft. Picture from the Gas Encyclopedia by Air Liquide.

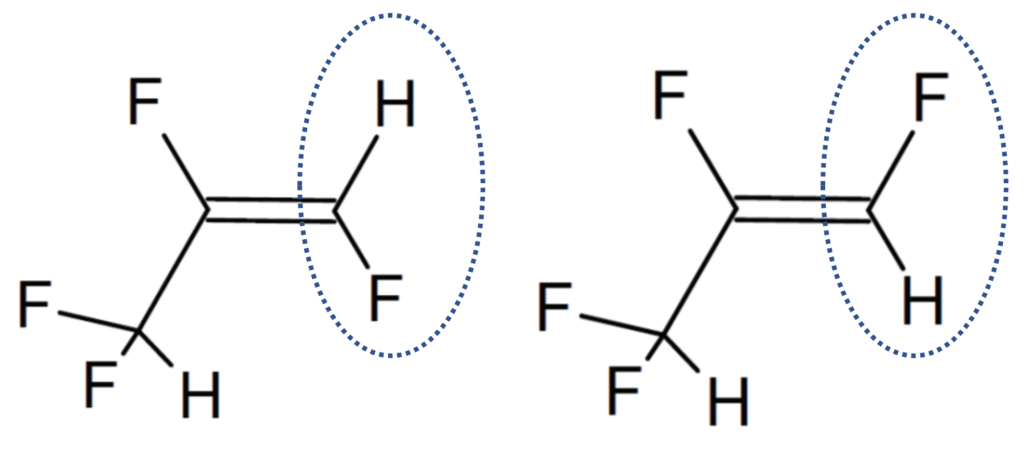

In the ASHRAE system for pure compounds, a letter designates the primary purpose of the compound, R for refrigerant, P for aerosol propellant, S for solvent, and the numbers are based on the chemical formula. Sometimes the letter is replaced with a trade name such as Freon. For blends, numbers are assigned sequentially based on ASHRAE data review completion date. For an ASHRAE designation, the first digit from the right is the number of fluorine atoms. The second digit from the right is the number of hydrogen atoms plus one. The third digit is the number of carbon atoms minus one; if this is a zero then that number would be omitted. The fourth digit is the number of unsaturated carbon-carbon bonds, in saturated compounds this number is omitted. If an upper-case B or I appears the number immediately following it is the number of bromine or iodine atoms respectively. There are often lowercase letters following the numeric designations. The first appended letter is for substitutions on the central carbon atom, an x represents a chlorine substitution, y for fluorine, and z for hydrogen. The second appended letter designates substitutions on the terminal methylene carbon, =CCl2 is -a, =CClF is -b, =CF2 is -c, =CHCl is -d, =CHF is -e, and =CH2 is -f. Isomers are also designated by a Z or an E appended to the name for “zusammen” or “entgegen” respectively. Zusammen is German for together and entgegen is opposite; they represent cis and trans isomers respectively.

Cyclic compounds (R300 series), ethers, inorganic fluids (R700 series), and miscellaneous organic compounds (R600 series) have additional rules. The series are specified so the 000 series are methane based compounds, 100 are ethane based, 200 are propane based, and 300 are cyclic. The 400 series are zeotropes and 500 are azeotropes. The 600 series are other organic compounds. The 700 series are inorganic refrigerants such as ammonia, also known as R-717. The 1000 series which are unsaturated organic compounds such as the new R-1234yf refrigerant. R-1234yf is used for about half of all automobiles built after 2018 and it breaks down into short chained perfluorinated carboxylic acids; specifically, trifluoroacetic acid.

There are other code systems in use that are more field dependent as well. For instance, chlorofluorocarbons have a numbering system as do halogenated fire extinguishers. The Halon numbering system is in comparison very easy; there are always four numbers and left to right the digits represent carbon, fluorine, chlorine, and bromine atoms present in the molecule. For instance, Halon-1211 (CF2ClBr also known as Freon-12B1) and Halon-1301 (CF3Br which would also be known as R-13B1). On 1 January 1994 the United States banned the import and production of halons 1211 and 1301 under the Clean Air Act to comply with the Montreal Protocol. These halons are still allowed to be used and recycled halons may be purchased. Both Halon 1211 and 1301 have Class A, B, and C ratings. Halon-1211 is a “streaming agent,” and more commonly used in hand-held extinguishers because it discharges mostly as a liquid stream. Halon-1301 is a “flooding agent” and discharges mostly as a gas, allowing it to penetrate tight spaces and behind obstacles making it ideal for enclosed spaces commonly found in aircraft. The United States owns about 40% of global halon-1301 supply and it will likely stay in use for many years worldwide. Halon-1301 is critical as it was formerly the only material usable in enclosed spaces where humans were present.

CAS nomenclature

CAS stands for Chemical Abstract Service (CAS) and it is a division of the American Chemical Society. A CAS number is a unique identifier assigned by CAS to every chemical substance. It includes isotopes, mixtures, alloys, and substances which have unknown or variable composition. CAS numbers do not contain information about the substance structure unlike all previously discussed naming systems, simplified molecular-input line-entry system (SMILES), or the IUPAC International Chemical Identifier (InChI) system.

The same PFAS chemical in different forms will have differing chemical properties because of structural differences. For example, PFOS (perfluorooctanesulfonic acid) in its acid form (C8HF17O3S) has a CAS number of 1763-23-1, its potassium salt (C8F17KO3S) 2795-39-3, and its ammonium salt (C8H4F17NO3S) 29081-56-9.

F-Nomenclature

F-nomenclature was accepted by the American Chemical Society as an alternative to perfluoro nomenclature because some early fluorochemistry pioneers disliked perfluoro nomenclature. JH Simons in particular disliked perfluoro nomenclature. Simons invented the electrochemical fluoridization processes which was the first industrial process for producing perfluorinated compounds.

In F-nomenclature perfluoropentanoic acid (PFPeA – a C5 fully saturated carboxylic acid) would be F-pentanoic acid. As an aside, C5H10O2 which is pentanoic acid, is also known as valeric acid because it is the cause of the unpleasant smell in valerian.

Some elements of this naming system have survived. For instance, the symbol -R which indicates an organic backbone sometimes is written -RF to indicate a perfluoro backbone. Also, placing an F internal to a benzene ring structure is a shorthand saying that all the bonds off the ring not otherwise indicated are fluorine instead of hydrogen. A forerunner to F-nomenclature used a phi (φ) but was generally similar to F-nomenclature.

Other less common nomenclature systems

In the 1970s, J.H. Simons, an early fluorochemistry pioneer, advocated for placing “for” before the final syllable in standard hydrocarbon nomenclature to convey it was perfluorinated. Organofluorine Chemistry gives the following examples: CF4 as methforane and the perfluorinated version of ethene, CF2=CF2 would be ethforene.

Conclusion and Key Take Aways

Most PFAS naming systems are designed to reveal information about the basic chemical structure or function and to facilitate communication. In industrial settings where not many PFAS are used simultaneously it can be easier to use codes to cut down on potential errors common in systematic names. It is important to understand the basic names within your specific use.

This article is one of several on PFAS. You can read about PFAS discovery, structure, or all my articles on PFAS.

3 thoughts on “PFAS Terminology and Nomenclature”