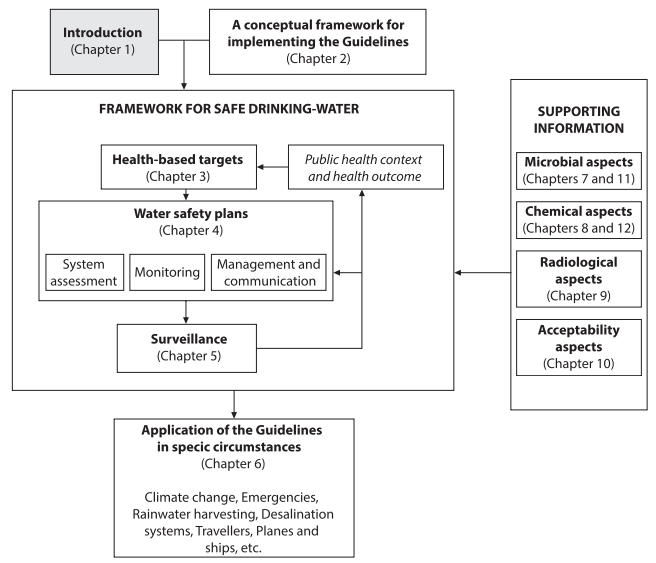

The World Health Organization (WHO) is considering adding PFOA and PFOS into its Guidelines for Drinking Water Quality and is seeking public comment on their background document for development of WHO Guidelines for Drinking Water Quality. This document is undergoing rolling revisions and accepting public comment using the form here sent to gdwq@who.int by 11 November 2022. Guidelines for Drinking Water Quality are essentially the WHO’s version of the US EPA’s Health Advisories however, are 5 orders of magnitude higher with 100 ppt individual guidelines for PFOA and PFOS as well as a 500 ppt total PFAS guideline. This 5 order of magnitude divergence between health agencies is primarily because the US EPA used epidemiological studies to define the reference dose while the WHO primarily relied on toxicology. Relying on toxicology, the “WHO considered that the uncertainties in identifying the key endpoint applicable to human health following exposure to PFOS and/or PFOA are too significant to derive a HBGV with confidence” (page 79) while the US EPA did not have that issue. The intent of this article is to go over what the WHO is, why it publishes drinking water quality guidelines, and the comments I submitted. Please remember that my views are my own and do not reflect my employer’s position!

What is the WHO?

The WHO serves to coordinate and guide public health policy on a global level. It started as the Office International d’Hygiène Publique (OIHP) or The International Office of Public Hygiene of President Wilson’s failed experiment, the League of Nations. After the League of Nations folded on 20 April 1946 many of its functions were eventually rolled into the Untied Nations including the WHO. The WHO has been heavily criticized for decades such as by its former leaders and think tanks. Criticism stepped up sharply during the ongoing corona virus pandemic. Despite all this, the WHO remains virtually the only true global consensus-building public health organization. While its influence has weakened in recent years due to other global public health actors such as the World Bank or the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, it still is one of the most broadly recognized and supported organizations dedicated to public health.

Why does the WHO publish drinking water quality guidelines?

The WHO itself has been publishing drinking water quality guidelines since 1958 and in fact the WHO’s grandparents were the International Sanitary Conferences (ISC) first held on 23 June 1851 which were established as a result of a cholera pandemic. The OIHP was initially established to carry out some of the ISC’s recommendations. Cholera is a waterborne disease; a fact made famous by John Snow and the Broad Street Pump. By removing a pump handle Dr. Snow helped deal a blow to the miasma theory of disease and served as a founding father to epidemiology; a subject I have a case study in.

Outside of this historical context, access to safe drinking water was voted a basic human right by the UN; whether or not a good/service can be considered a right is a discussion for a different day.

What are the WHO Guideline Values?

The WHO currently recommends individual provisional guidance values of 100 ppt for PFOS and PFOA as well as 500 ppt for total PFAS. These numbers exactly mirror the EU Drinking Water Directive and are substantially higher than the US EPA recommendations which are 0.004 ppt (or 4 parts per quadrillion) and 0.02 ppt (or 20 parts per quadrillion) for PFOA and PFOS respectively. A key reason why these values are so dramatically different is that the US EPA considered epidemiological studies while the WHO did not.

Throughout the document the WHO uses older thoughts on PFAS and consistently cites the 2016 health advisories. The US EPA has the most current human health toxicity assessments for PFAS however, the WHO consistently lists them last.

On page 63 the WHO states (the numbers in the quote are line numbers for that page) “PFOA exposure is associated with clear 23 evidence of carcinogenic activity in male rats based on the increased incidence of liver 24 adenomas and pancreatic acinar cell tumours.” It is therefore not possible using current evidence 25 to exclude PFOA as a human carcinogen”. This wording reflects the US EPA’s 2016 position; more recent human and animal studies lead the US EPA to conclude that PFOA is a more potent carcinogen than previously thought.

I am not enough of a health scientist to know or provide a meaningful analysis on the health aspects of the document other than the superficial one I just provided pointing out the WHO is using older science. Normally in the debate between epidemiology and toxicology, toxicology points to a more dangerous substance than the epidemiological studies. Here, due to the preferred analysis by these organizations it appears to be flip flopped. I would personally prefer to err on the side of caution; especially since drinking water according to the UN is a fundamental human right.

Why I submitted comments to the WHO

Simply put the WHO generally listens if you have a well thought out valid point which conforms to their purpose. During their last request for comment I (and probably quite a few other people) made quite a few recommendations which were incorporated into this draft document. For example, I recommended they:

- Take into account Xiao’s paper which shows that PFAS can be generated during advanced oxidation processes. This also changed their practical considerations on monitoring so was quite a substantial change to the document.

- Take out the octanol water partitioning coefficient (Kow) from their table of physicochemical properties because PFOA and PFOS are both hydro- and lithophobic so bifurcate into its own layer between octanol and water. Although some people report values, these values are not reflective of the ground truth since the standard test was not designed for that type of material. They also changed some of the other values such as the boiling point and melting point because the predicted range was larger than the experimental range.

- Specify that anion exchange deals with anionic PFAS since there are cationic and neutral PFAS so there were some changes to those sections as a result.

- Drop the “s” from the PFAS acronym for plurals because a substance cannot simultaneously be per- and polyfluorinated so the plural is already implied.

- Use the OECD definition of PFAS which they updated.

- Use updates I provided on page 71 about characterizing EPA methods 533 and 537.1

One of my comments was almost incorporated word for word on page 74 related to chain length and functional group removal efficacy; a conclusion I partially took from this Sörengård et al. paper.

Previous comments which were not accepted

Not all my previous comments were accepted. This goes to reflect that two people can look at the same data and draw different conclusions. Especially when the topic is a matter of policy there is often no “correct” answer although there are often clear cut “incorrect” answers. I am going to use this section to highlight some of the comments I made which were rejected, why I made those comments, and potentially the reason why the comment was rejected.

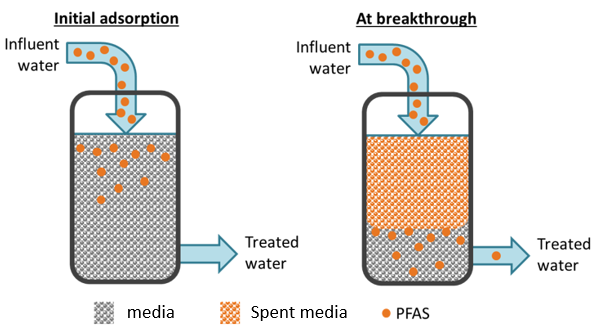

- I recommended against using percent removal as a characterization of process efficiency. You can think of properly designed granular activated carbon or anion exchange beds as towels wiping up liquid (contaminant). When the towel is dry and the spill is small it picks up all of it quickly. A wet towel mopping up a large spill may not clean everything or may not clean it quickly. Try and keep that analogy in mind for a contactor. The photo below shows one mode for thinking of breakthrough. Better ways to characterize the efficiency are to use media usage rate or bed life. I believe that the WHO used percent removal because it makes it easier to compare to membrane filtration although again, I disagree with this characterization.

- I provided references which show greater removal percentages for sorption that the WHO quotes. There are many however, the US EPA drinking water treatability database captures many such examples. The WHO is also much more pessimistic on anion exchange than I believe is warranted based on the data. There are both full scale, pilot, and bench studies included. I do not really know why the WHO was cautious there compared to their membrane section where results were more often accepted at face value except potentially that was due to the declining efficacy over bed life which again, is why I suggested percent removal is a bad way to measure sorption process efficiency.

- The WHO focuses on source water monitoring. In general, this is a good approach however, I do not agree with it for PFAS. PFAS is not known to and is unlikely to leach or permeate into drinking water supply. Likewise, PFAS can be generated during treatment when advanced oxidation (and potentially advanced reduction) processes are used. If resources are constrained it makes more sense to me to monitor the finished water rather than source water if only one is to be monitored especially since source waters are unlikely to change. The counter argument is that only specific wells could be contaminated, and it would make sense to shut down those wells and not have to treat. If you only monitor finished water, you will miss that level of detail. If resources are constrained and you only monitor the influent, you’ll miss that anyway. To me, this is a good example of two reasonable policy positions based on the same facts with divergent conclusions.

- In the previous document, the WHO referenced replacement chemistries; specifically short chained PFAS. I recommended that esterified replacement chemistries be mentioned as well such as HFPO-DA (also known as GenX chemicals), ADONA, and Nafion byproducts. Instead, the WHO removed references to replacement chemistries. This is a good compromise because there are many replacement chemistries available.

My comments on the current draft

On this new draft the comments I have submitted to the WHO using their form emailing to gdwq@who.int (11 November 2022 deadline) are:

- The recommendation on page 70 that PFAS monitoring is only required when there is a reasonable source nearby is not protective of public health or in the best interests of society at large. As this document points out PFAS is capable of long-range transport and deposition. PFAS has been found in the artic and Antarctic as well as other remote areas. Additionally, airports; military sites; landfills; wastewater treatment plants; carpet, upholstery, wax, and paper product manufacturers; or spreading biosolids (composting) are all PFAS sources. Rasstadt, Germany was contaminated with composting from used food containers for example. I do not believe that you can successfully perform a risk assessment given the diverse set of sources, low toxicity thresholds, and long-range transport capabilities.

- Page 72 lines 8-9 state (line numbers in parathesis): “Blending or diluting PFAS contaminated source water with uncontaminated water may be a (9) cost-effective and viable option for some water systems.” As there is ultra-low toxicity and PFOA as well as PFOS have been identified as likely carcinogens I do not believe that deliberately exposing people to these contaminants through diluting or blending is an appropriate course of action unless there are no other alternatives such as treatment (this would be an economics question) or source substitution.

- Page 76 provides information on PFAS removal through sorptive technologies. I believe, and have provided references above in this article, that significantly lower treatment standards are possible.

- On page 16 lines 27-30 it states (line numbers in quotes): “In 2019, the US EPA conducted a broad literature search to evaluate (28) evidence for pathways of human exposure to PFOA and PFOS, and in 2021 released a draft (29) analysis that supports application of a 20 percent relative source contribution for PFOA and (30) PFOS in drinking water (US EPA, 2021b,c).” This seems to overstate the strength of the conclusion the EPA made in those health advisories. As I mention in this article, the EPA’s position was that there was insufficient evidence to deviate from a 20% default value; not that evidence supported a particular value.

- On page 4 line 37-39 it states (line number in parentheses): “PFOA remains possible, even where it is no longer (38) manufactured or used due to its legacy uses, degradation of precursors, and extremely high (39) persistence in the environment and the human body.” I believe this is also true for PFOS and that disclaimer should be added to that section as well.

- Page 74 lines 45-46 deal with anion exchange resin regeneration. Greater than 95% resin regeneration has been demonstrated in literature here, here, and here although it may not be practical for utilities from a safety and/or cost prospective.

- On page 9, the WHO references this Boone et al study; when the study was published the conclusion that only one monitored drinking water plan exceeded the EPA’s HAs was valid however, the HAs were updated. That changes the study conclusion from one drinking water plan exceeding the EPA’s HAs to all quantitatively monitored plants exceeding the HAs, a significantly different conclusion.

Conclusion and Key Take Aways

Over time, scientific consensus points to greater and greater awareness of the dangers PFAS pose. Generally, we thought these chemicals were safer in the past than most scientists do today. The WHO, in its role as a policy leader, has developed a significantly less stringent health recommendation than even the old 2016 US EPA HAs on the dangers of these chemicals by not weighting epidemiological evidence the same way. The WHO standard exactly mirrors the EU standard under the drinking water directive. The WHO is a reasonable organization and solicits public comment and feedback as well as generally listening to it. I highly recommend you share your opinions with the WHO regardless of whether you agree with me and take an active role in global public health.

Further Reading

This is one of several articles on PFAS I have written. You can read about PFAS discovery, structure, or all my articles on PFAS.